The Functions And Forms Of Masks

The Functions And Forms Of Masks

Masks are as extraordinarily varied in appearance as they are in function or fundamental meaning. Many masks are primarily associated with ceremonies that have religious and social significance or are concerned with funerary customs, fertility rites, or curing sickness. Other masks are used on festive occasions or to portray characters in a dramatic performance and in re-enactments of mythological events. Masks are also used for warfare and as protective devices in certain sports, as well as frequently being employed as architectural ornament.

Social And Religious Uses

Masks representing potentially harmful spirits were often used to keep a required balance of power or a traditional relationship of inherited positions within a culture. The forms of these masks invariably were prescribed by tradition, as were their uses. This type of mask was often associated with secret societies, especially in Africa, where the greatest range of types and functions can be found. They were also widely used among Oceanic peoples of the South Pacific and the American Indians and are even used in some of the folk rites still performed in Europe.

Masks have served an important role as a means of discipline and have been used to admonish women, children, and criminals. Common in China, Africa, Oceania, and North America, admonitory masks usually completely cover the features of the wearer. It is believed among some of the African Negro tribes that the first mask was an admonitory one. A child, repeatedly told not to, persisted in following its mother to fetch water. To frighten and discipline the child, the mother painted a hideous face on the bottom of her water gourd.

Others say the mask was invented by a secret African society to escape recognition while punishing marauders. In New Britain, members of a secret terroristic society called the Dukduk appear in monstrous five-foot masks to police, to judge, and to execute offenders. Aggressive supernatural spirits of an almost demonic nature are represented by these masks, which are constructed from a variety of materials, usually including tapa, or bark cloth, and the pith of certain reeds. These materials are painted in brilliant colours, with brick red and acid green predominating.

In many cultures throughout the world, a judge wears a mask to protect him from future recriminations. In this instance, the mask represents a traditionally sanctioned spirit from the past who assumes responsibility for the decision levied on the culprit.

Rituals, often nocturnal, by members of secret societies wearing ancestor masks are reminders of the ancient sanction of their conduct. In many cultures, these masked ceremonials are intended to prevent miscreant acts and to maintain the circumscribed activities of the tribe. Along the Guinea coast of West Africa, for instance, many highly realistic masks represent ancestors who enjoyed specific cultural roles; the masks symbolize sanction and control when donned by the wearer.

Among some of the Dan and Ngere tribes of Liberia and Ivory Coast, ancestor masks with generic features act as intermediaries for the transmission of petitions or offerings of respect to the gods. These traditional ancestral emissaries exert by their spirit power a social control for the community.

Particularly among Oceanic peoples, American Indians, and Negro tribes of Africa, certain times of the year are set aside to honour spirits or ancestors. Among nonliterate peoples who cannot record their own histories, masked rituals act as an important link between past and present, giving a sense of historic continuity that strengthens their social bond. On these occasions, masks usually recognizable as dead chieftains, relatives, friends, or even foes are worn or exhibited. Gifts are made to the spirits incarnated in the masks, while in other instances dancers wearing stylized mourning masks perform the prescribed ceremony.

In western Melanesia, the ancestral ceremonial mask occurs in a great variety of forms and materials. The Sepik River area in north central New Guinea is the source of an extremely rich array of these mask forms mostly carved in wood, ranging from small faces to large fantastic forms with a variety of appendages affixed to the wood, including shell, fiber, animal skins, seed, flowers, and feathers. These masks are highly polychromed with earth colours of red and yellow, lime white, and charcoal black. They often represent supernatural spirits as well as ancestors and therefore have both a religious and a social significance.

Members of secret societies usually conduct the rituals of initiation, when a young man is instructed in his future role as an adult and is acquainted with the rules controlling the social stability of the tribe. Totem and spiritualistic masks are donned by the elders at these ceremonies. Sometimes the masks used are reserved only for initiations. Among the most impressive of the initiation masks are the exquisitely carved human faces of west coast African Negro tribes.

In western and central Congo (Kinshasa), in Africa, large, colourful helmetlike masks are used as a masquerading device when the youth emerges from the initiation area and is introduced to the villagers as an adult of the tribe. After a lengthy ordeal of teaching and initiation rites, for instance, a youth of the Pende tribe appears in a distinctive colourful mask indicative of his new role as an adult. The mask is later cast aside and replaced by a small ivory duplicate, worn as a charm against misfortune and as a symbol of his manhood.

The Functions And Forms Of Masks

Believing everything in nature to possess a spirit, man found authority for himself and his family by identifying with a specific nonhuman spirit. He adopted an object of nature; then he mythologically traced his ancestry back to the chosen object; he preempted the animal as the emblem of himself and his clan. This is the practice of totem, which consolidates family pride and distinguishes social lines. Masks are made to house the totem spirit. The totem ancestor is believed actually to materialize in its mask; thus masks are of the utmost importance in securing protection and bringing comfort to the totem clan.

The Papuans of New Guinea build mammoth masks called hevehe, attaining 20 feet in height. They are constructed of a palm wood armature covered in bark cloth; geometric designs are stitched on with painted cane strips. These fantastic man–animal masks are given a frightening aspect. When they emerge from the men’s secret clubhouse, they serve to protect the members of the clan.

The so-called “totem” pole of the Alaskan and British Columbian Indian fulfills the same function. The African totem mask is often carved from ebony or other hard woods, designed with graceful lines and showing a highly polished surface. Animal masks, their features elongated and beautifully formalized, are common in western Africa. Dried grass, woven palm fibers, coconuts, and shells, as well as wood are employed in the masks of New Guinea, New Ireland, and New Caledonia. Represented are fanciful birds, fishes, and animals with distorted or exaggerated features.

The high priest and medicine man, or the shaman, frequently had his own very powerful totem, in whose mask he could exorcise evil spirits, punish enemies, locate game or fish, predict the weather, and, most importantly, cure disease.

The Northwest Coast Indians of North America in particular devised mechanical masks with movable parts to reveal a second face—generally a human image. Believing that the human spirit could take animal form and vice versa, the makers of these masks fused man and bird or man and animal into one mask. Some of these articulating masks acted out entire legends as their parts moved.

Types of Masks

- African tribal masks

- Character mask

- Clown Mask by Patch Adams

- Medical Masks

- Plague doctor masks

- Ritual masks

- Sport Masks

- The Sleep Mask

- Theater Masks – Comedy and Tragedy

- The Functions And Forms Of Masks

Funerary And Commemorative Uses

In cultures in which burial customs are important, anthropomorphic masks have often been used in ceremonies associated with the dead and departing spirits. Funerary masks were frequently used to cover the face of the deceased. Generally their purpose was to represent the features of the deceased, both to honour them and to establish a relationship through the mask with the spirit world. Sometimes they were used to force the spirit of the newly dead to depart for the spirit world. Masks were also made to protect the deceased by frightening away malevolent spirits.

From the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1786 BC) to the 1st century AD, the ancient Egyptians placed stylized masks with generalized features on the faces of their dead. The funerary mask served to guide the spirit of the deceased back to its final resting place in the body. They were commonly made of cloth covered with stucco or plaster, which was then painted. For more important personages, silver and gold were used. Among the most splendid examples of the burial portrait mask is the one created c. 1350 BC for the pharaoh Tutankhamen. In Mycenaean tombs of c. 1400 BC, beaten gold portrait masks were found. Gold masks also were placed on the faces of the dead kings of Cambodia and Siam.

The mummies of Inca royalty wore golden masks. The mummies of lesser personages often had masks that were made of wood or clay. Some of these ancient Andean masks had movable parts, such as the metallic death mask with movable ears that was found in the Moon Pyramid at Moche, Peru. The ancient Mexicans made burial masks that seem to be generic representations rather than portraits of individuals.

In ancient Roman burials, a mask resembling the deceased was often placed over his face or was worn by an actor hired to accompany the funerary cortege to the burial site. In patrician families these masks or imagines were sometimes preserved as ancestor portraits and were displayed on ceremonial occasions. Such masks were usually modeled over the features of the dead and cast in wax. This technique was revived in the making of effigy masks for the royalty and nobility of Europe from the late Middle Ages through the 18th century.

Painted and with human hair, these masks were attached to a dummy dressed in state regalia and were used for display, processionals, or commemorative ceremonials. From the 17th century to the 20th, death masks of famous persons became widespread among European peoples. With wax or liquid plaster of paris, a negative cast of the human face could be produced that in turn acted as a mold for the positive image, frequently cast in bronze. In the 19th century, life masks made in the same manner became popular.

Another type of life mask had been produced in the Fayyum region of Egypt during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. These were realistic portraits painted in encaustic on wood during a person’s lifetime; when the person died, they were attached directly to the facial area on the mummy shroud.

The skull mask is another form usually associated with funerary rites. The skull masks of the Aztecs, like their wooden masks, were inlaid with mosaics of turquoise and lignite, and the eye sockets were filled with pyrites. Holes were customarily drilled in the back so the mask might be hung or possibly worn. In Melanesia, the skull of the deceased is often modeled over with clay, or resin and wax, and then elaborately painted with designs that had been used ceremonially by the deceased during his own lifetime.

The Functions And Forms Of Masks

Therapeutic Uses

Masks have played an important part in magico-religious rites to prevent and to cure disease. In some cultures, the masked members of secret societies could drive disease demons from entire villages and tribes. Among the best known of these groups was the False Face Society of the North American Iroquois Indians. These professional healers performed violent pantomimes to exorcise the dreaded Gahadogoka gogosa (demons who plagued the Iroquois). They wore grimacing, twisted masks, often with long wigs of horsehair. Metallic inserts often were used around the eyes to catch the light of the campfire and the moon, emphasizing the grotesqueness of the mask.

Masks for protection from disease include the measle masks worn by Chinese children and the cholera masks worn during epidemics by the Chinese and Burmese. The disease mask is most developed among the Sinhalese in Sri Lanka (Ceylon), where 19 distinct rakasa, or disease devil masks, have been devised. These masks are of ferocious aspect, fanged, and with startling eyes. Gaudily coloured and sometimes having articulating jaws, they present a dragon-like appearance.

Masks have long been used in military connections. A war mask will have a malevolent expression or hideously fantastic features to instill fear in the enemy. The ancient Greeks and Romans used battle shields with grotesque masks or attached terrifying masks to their armour, as did the Chinese warrior. Grimacing menpo, or mask helmets, were used by Japanese samurai.

Many sports require the use of masks. Some of these are merely functional, protective devices such as the masks worn by fencers, baseball catchers, or even skiers. To protect their faces in sports events and tournaments of arms, horsemen of the Roman army attached highly decorative and symbolic masks to their helmets.

Perhaps the earliest use of masks was in connection with hunting. Disguise masks were seemingly used in the early Stone Age in stalking prey and later to house the slain animal’s spirit in the hope of placating it. The traditional animal masks worn by the Altaic and Tungusic shamans in Siberia are strictly close to such prehistoric examples as the image of the so-called sorcerer in the Cave of Les Trois Frères in Ariège, France.

Since agricultural societies first appeared in prehistory, the mask has been widely used for fertility rituals. The Iroquois, for instance, used corn husk masks at harvest rituals to give thanks for and to achieve future abundance of crops. Perhaps the most renowned of the masked fertility rites held by American Indians are those still performed by the Hopi and Zuni Indians of the Southwest U.S. Together with masked dancers representing clouds, rain spirits, stars, Earth Mother, sky god, and others, the shaman takes part in elaborate ceremonies designed to assure crop fertility.

Spirits called kachinas, who first brought rain to the Pueblo tribes, are said to have left their masks behind when sent to dwell in the bottom of a desert lake. Their return to help bring the rain is incarnated by the masked dancer. Cylindrical masks, covering the entire head and resting on the shoulders, are of a primal type. They are made of leather and humanized by the addition of hair and a variety of adjuncts. Eyes are represented by incisions or by buckskin balls filled with deer hair and affixed to the mask. The nose is often of rolled buckskin or corncob.

Frequently the mask has a projecting wooden cylinder for a bill or a gourd stem cut with teeth for a snout. Horns are attached to some masks. Many colours are used in their painting; plumes and beads are attached, and the sex of the mask is distinguished by its shape: round head indicates male and square indicates female. In the western Sudan area of Africa many tribes have masked fertility ceremonials. The segoni-kun masks that are fashioned by the Bambara tribes in Mali are aesthetically among the most interesting.

Antelopes, characterized by their elegant simplicity, are carved in wood and affixed to woven fiber caps that are hung with raffia and cover the wearer. The antelope is believed to have introduced agriculture, and so when crops are sown, members of Tji-wara society cavort in the fields in pairs to symbolize fertility and abundance.

Festive Uses

Masks for festive occasions are still commonly used in the 20th century. Ludicrous, grotesque, or superficially horrible, festival masks are usually conducive to good-natured license, release from inhibitions, and ribaldry. These include the Halloween, Mardi Gras, or “masked ball” variety. The disguise is assumed to create a momentary, amusing character, often resulting in humorous confusions, or to achieve anonymity for the prankster or ribald reveler.

Throughout contemporary Europe and Latin America, masks are associated with folk festivals, especially those generated by seasonal changes or marking the beginning and end of the year. Among the most famous of the folk masks are the masks worn to symbolize the driving away of winter in parts of Austria and Switzerland. In Mexico and Guatemala, annual folk festivals employ masks for storytelling and caricature, such as for the Dance of the Old Men and the Dance of the Moors and the Christians. The Eskimo make masks with comic or satiric features that are worn at festivals of merrymaking, as do the Ibos of Nigeria.

Theatrical Uses

Masks have been used almost universally to represent characters in theatrical performances. Theatrical performances are a visual literature of a transient, momentary kind. It is most impressive because it can be seen as a reality; it expends itself by its very revelation. The mask participates as a more enduring element, since its form is physical.

The mask as a device for theatre first emerged in Western civilization from the religious practices of ancient Greece. In the worship of Dionysus, god of fecundity and the harvest, the communicants’ attempt to impersonate the deity by donning goatskins and by imbibing wine eventually developed into the sophistication of masking. When a literature of worship appeared, a disguise, which consisted of a white linen mask hung over the face (a device supposedly initiated by Thespis, a 6th-century-BC poet who is credited with originating tragedy), enabled the leaders of the ceremony to make the god manifest. Thus symbolically identified, the communicant was inspired to speak in the first person, thereby giving birth to the art of drama.

In Greece the progress from ritual to ritual-drama was continued in highly formalized theatrical representations. Masks used in these productions became elaborate headpieces made of leather or painted canvas and depicted an extensive variety of personalities, ages, ranks, and occupations. Heavily coiffured and of a size to enlarge the actor’s presence, the Greek mask seems to have been designed to throw the voice by means of a built-in megaphone device and, by exaggeration of the features, to make clear at a distance the precise nature of the character.

Moreover, their use made it possible for the Greek actors—who were limited by convention to three speakers for each tragedy—to impersonate a number of different characters during the play simply by changing masks and costumes. Details from frescoes, mosaics, vase paintings, and fragments of stone sculpture that have survived to the present day provide most of what is known of the appearance of these ancient theatrical masks. The tendency of the early Greek and Roman artists to idealize their subjects throws doubt, however, upon the accuracy of these reproductions. In fact, some authorities maintain that the masks of the ancient theatre were crude affairs with little aesthetic appeal.

Masks info

- Masking

- Masking in Psychology

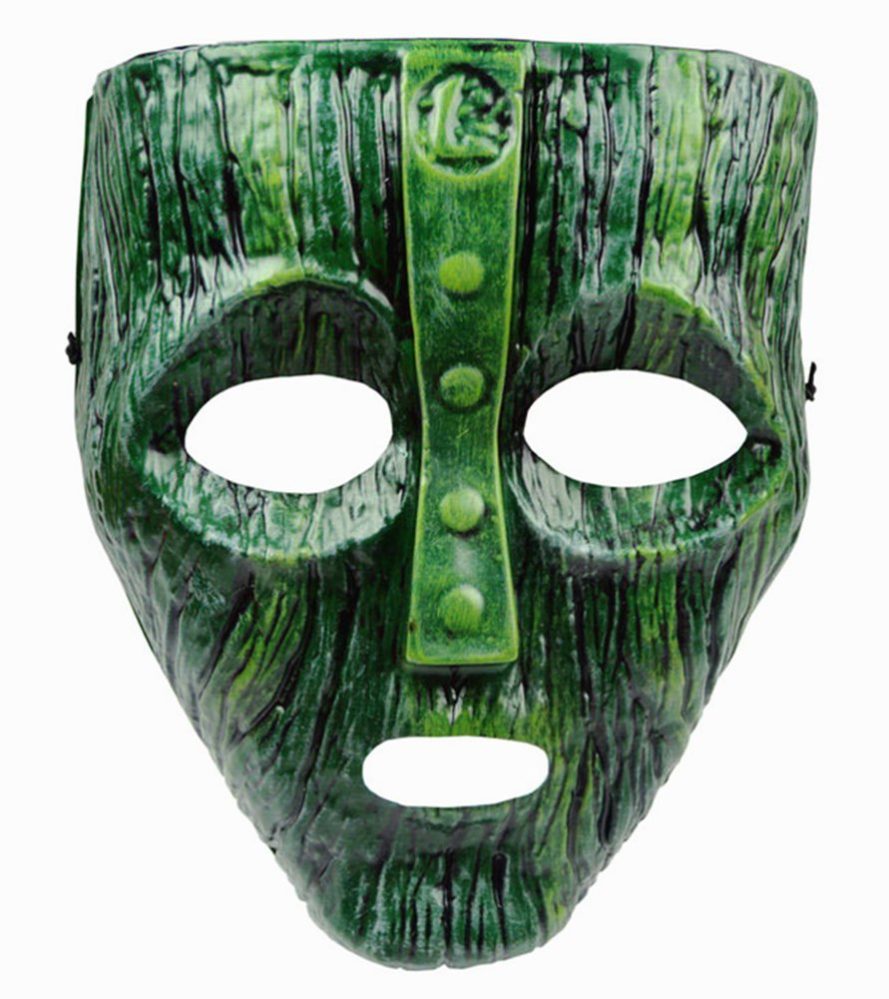

- Mask of Loki

- Mask the movie

- Ritual masks

- The Functions And Forms Of Masks

- What is the Mask?

- Clown Mask by Patch Adams

- The Sleep Mask

In the Middle Ages, masks were used in the mystery plays of the 12th to the 16th century. In plays dramatizing portions of the Old and New Testaments, grotesques of all sorts, such as devils, demons, dragons, and personifications of the seven deadly sins, were brought to stage life by the use of masks. Constructed of papier-mâché, the masks of the mystery plays were evidently marvels of ingenuity and craftsmanship, being made to articulate and to belch fire and smoke from hidden contrivances. But again, no reliable pictorial record has survived.

Masks used in connection with present-day carnivals and Mardi Gras and those of folk demons and characters still used by central European peasants, such as the Perchten masks of Alpine Austria, are most likely the inheritors of the tradition of medieval masks.

The 15th-century Renaissance in Italy witnessed the rise of a theatrical phenomenon that spread rapidly to France, to Germany, and to England, where it maintained its popularity into the 18th century. Comedies improvised from scenarios based upon the domestic dramas of the ancient Roman comic playwrights Plautus (254?–184 BC) and Terence (186/185–159 BC) and upon situations drawn from anonymous ancient Roman mimes flourished under the title of commedia dell’arte.

Adopting the Roman stock figures and situations to their own usage’s, the players of the commedia were usually masked. Sometimes the masking was grotesque and fanciful, but generally a heavy leather mask, full or half face, disguised the commedia player. Excellent pictorial records of both commedia costumes and masks exist; some sketches show the characters of Arlecchino and Colombina wearing black masks covering merely the eyes, from which the later masquerade mask is certainly a development.

Except for vestiges of the commedia in the form of puppet and marionette shows, the drama of masks all but disappeared in Western theatre during the 18th, 19th, and first half of the 20th centuries. In modern revivals of ancient Greek plays, masks have occasionally been employed, and such highly symbolic plays as Die versunkene Glocke (The Sunken Bell; 1897) by the German Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) and dramatizations of Alice in Wonderland have required masks for the performers of grotesque or animal figures.

The Irish poet-playwright W.B. Yeats (1865–1939) revived the convention in his Dreaming of the Bones and in other plays patterned upon the Japanese No drama. In 1926 theatre goers in the United States witnessed a memorable use of masks in The Great God Brown by the American dramatist Eugene O’Neill (1888–1953), wherein actors wore masks of their own faces to indicate changes in the internal and external lives of their characters. Oskar Schlemmer (1888–1943), a German artist associated with the Bauhaus, became interested in the late 1920s and ’30s in semantic phenomenology as applied to the design of masks for theatrical productions.

Modern art movements are often reflected in the design of contemporary theatrical masks. The stylistic concepts of Cubism and Surrealism, for example, are apparent in the masks executed for a 1957 production of La favola del figlio cambiato (The Fable of the Transformed Son) by the Italian dramatist Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936). A well-known mid-century play using masks was Les Nègres (1958; The Blacks, 1960) by the French writer Jean Genet. The mask, however, has unquestionably lost its importance as a theatrical convention in the 20th century, and its appearance in modern plays is unusual.

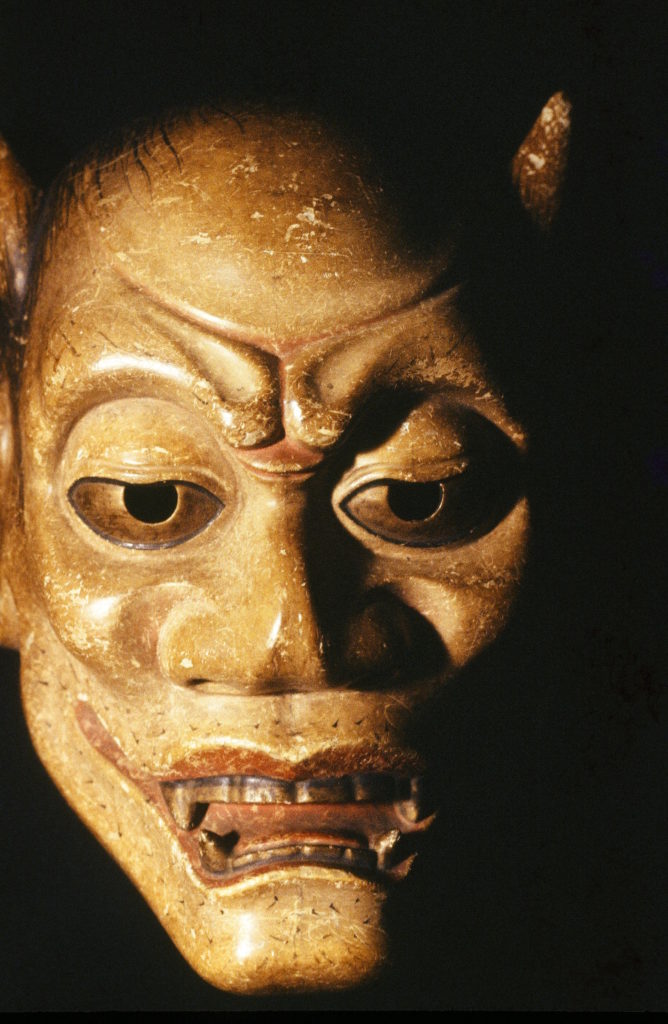

In many ways akin to Greek drama in origin and theme, the No drama of Japan has remained a significant part of national life since its beginnings in the 14th century. No masks, of which there are about 125 named varieties, are rigidly traditional and are classified into five general types: old persons (male and female), gods, goddesses, devils, and goblins. The material of the No mask is wood with a coating of plaster, which is lacquered and gilded. Colours are traditional.

White is used to characterize a corrupt ruler; red signifies a righteous man; a black mask is worn by the villain, who epitomizes violence and brutality. No masks are highly stylized and generally characterized. They are exquisitely carved by highly respected artists known as tenka-ichi, “the first under heaven.” Shades of feeling are portrayed with beautifully sublimated realism. When the masks are subtly moved by the player’s hand or body motion, their expression appears to change.

In Tibet, sacred dramas are performed by masked lay actors. A play for exorcising demons called the “Dance of the Red Tiger Devil” is performed at fixed seasons of the year exclusively by the priests or lamas wearing awe-inspiring masks of deities and demons. Masks employed in this mystery play are made of papier-mâché, cloth, and occasionally gilt copper. In the Indian state of Sikkim and in Bhutan, where wood is abundant and the damp climate is destructive to paper, they are carved of durable wood. All masks of the Himalayan peoples are fantastically painted and are usually provided with wigs of yak tail in various colours. Formally they often emphasize the hideous.

Masks, usually made of papier-mâché, are employed in the religious or admonitory drama of China; but for the greater part the actors in popular or secular drama make up their faces with cosmetics and paint to resemble masks, as do the Kabuki actors in Japan. The makeup mask both identifies the particular character and conveys his personality. The highly didactic sacred drama of China is performed with the actors wearing fanciful and grotesque masks. Akin to this “morality” drama are the congratulatory playlets, pageants, processions, and dances of China. Masks employed in these ceremonies are highly ornamented, with jeweled and elaborately filigreed headgears.

In the lion and dragon dances of both China and Japan, a stylized mask of the beast is carried on a pole by itinerant players, whose bodies are concealed by a dependent cloth. The mask and cloth are manipulated violently, as if the animal were in pursuit, to the taps of a small drum. The mask’s lower jaw is movable and made to emit a loud continuous clacking by means of a string.

On Java and Bali, wooden masks, tupeng, are used in certain theatrical performances called wayang wong. These dance dramas developed from the shadow puppet plays of the 18th century and are performed not only as amusement but as a safeguard against calamities. The stories are in part derived from ancient Sanskrit literature, especially the Hindu epics, although the Javanese later became Muslims.

The brightly painted masks are made of wood and leather and are often fitted with horsehair and metallic or gilded paper accoutrements. They are ordinarily held in the teeth by means of a strap of leather or rattan that has been fastened across the inside. Occasionally an actor interrupts the unseen narrator, the Dalang, who is speaking the play. The mask is then held in front of the face while the player says his line. The use of theatrical masks in Java is exceptional, since masks, being forbidden under the prohibition of images, are practically unknown in the Islamic world.

In the 20th century, with the breaking down of primitive and folk cultures, the mask has increasingly become a decorative object, although it has long been used in art as an ornamental device. In Haiti, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kenya, and Mexico, masks are produced largely for tourists. The collecting of old masks has been a part of the current interest in so-called primitive and folk arts. Masks also have exerted a decided influence on modern art movements, especially in the first decades of the 20th century, when painters in France and Germany found a source of inspiration in the tribal masks of Africa and western Oceania.

The Functions And Forms Of Masks

Additional Reading

“Masks” in the Encyclopedia of World Art, vol. 9, col. 520–570 (1964), a good historical survey;

William N. Fenton, “Masked Medicine Societies of the Iroquois,” Smithsonian Institution, Annual Report for 1940, pp. 397–429 (1941), a very good general discussion of Iroquois masks, with illustrations;

Marcel Griaule, Masques Dogons, 2nd ed. (1963), a profusely illustrated classic study of the masks of the Dogon, a people of Mali, within their cultural setting;

George W. Harley, Masks as Agents of Social Control in Northeast Liberia, Peabody Museum Papers 32, no. 2 (1950, reprinted 1975), a useful, illustrated article on this topic;

Edward A. Kennard, Hopi Kachinas, 2nd ed. (1971), an important study;

Dorothy J. Ray, Eskimo Masks: Art and Ceremony (1967), one of the best studies of Eskimo masks, with many fine plates and a bibliography;

F.E. Williams, Drama of Orokolo (1940, reprinted 1969), a classic study of masks of the Gulf of Papua, New Guinea, with fine illustrations and a bibliography;

Malcolm Kirk, Man as Art: New Guinea (1981), with especially good photographs;

Donald B. Cordry, Mexican Masks (1980), a study of how Mexican masks are related to both the European and the Indian traditions;

Simon Ottenberg, Masked Rituals of Afikpo (1975), a survey of a Nigerian masquerade tradition; and Leon Underwood, Masks of West Africa (1948), a small book but important for the subject, with good plates. Paul S. Wingert

“Reproduced with permission from the Encyclopaedia Britannica @ 1998-2000 Britannica.com Inc. All rights reserved.”