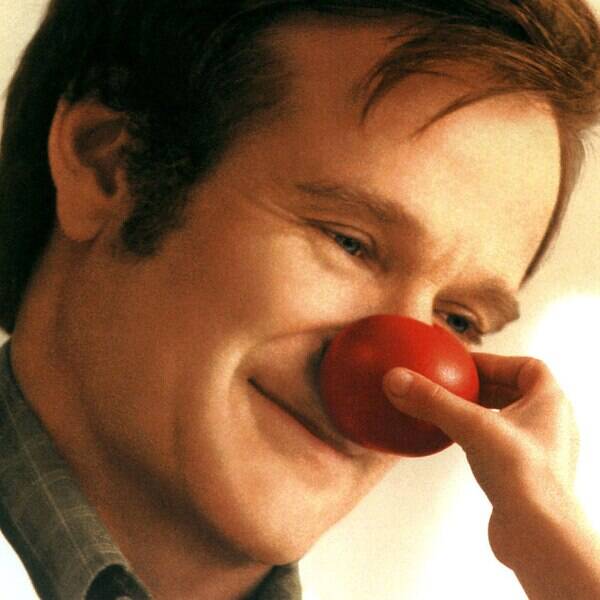

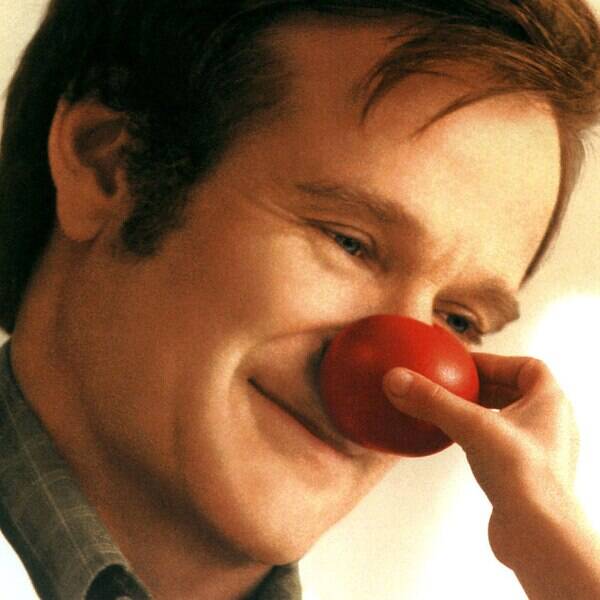

Clown Mask by Patch Adams

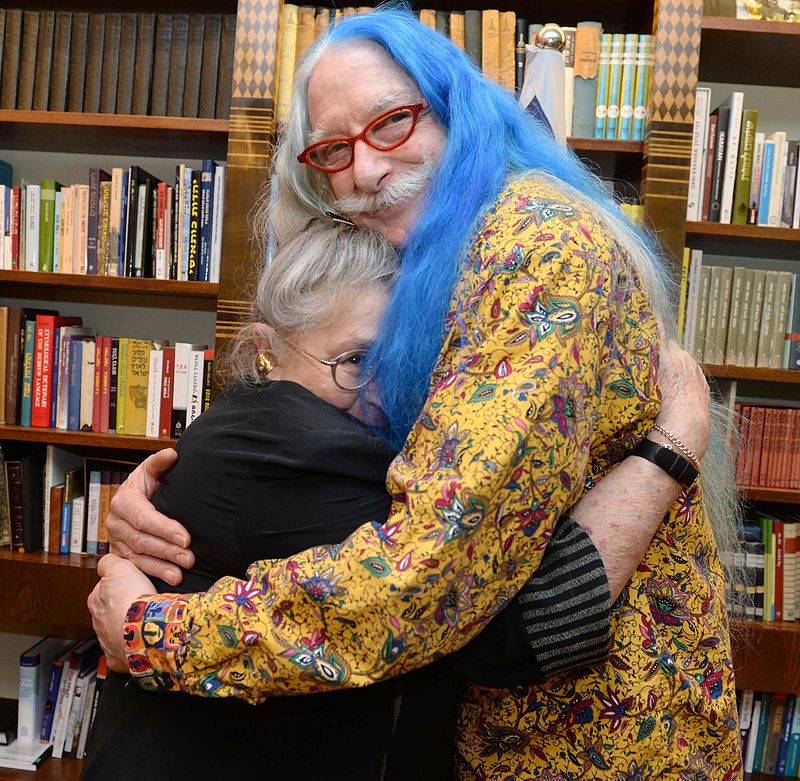

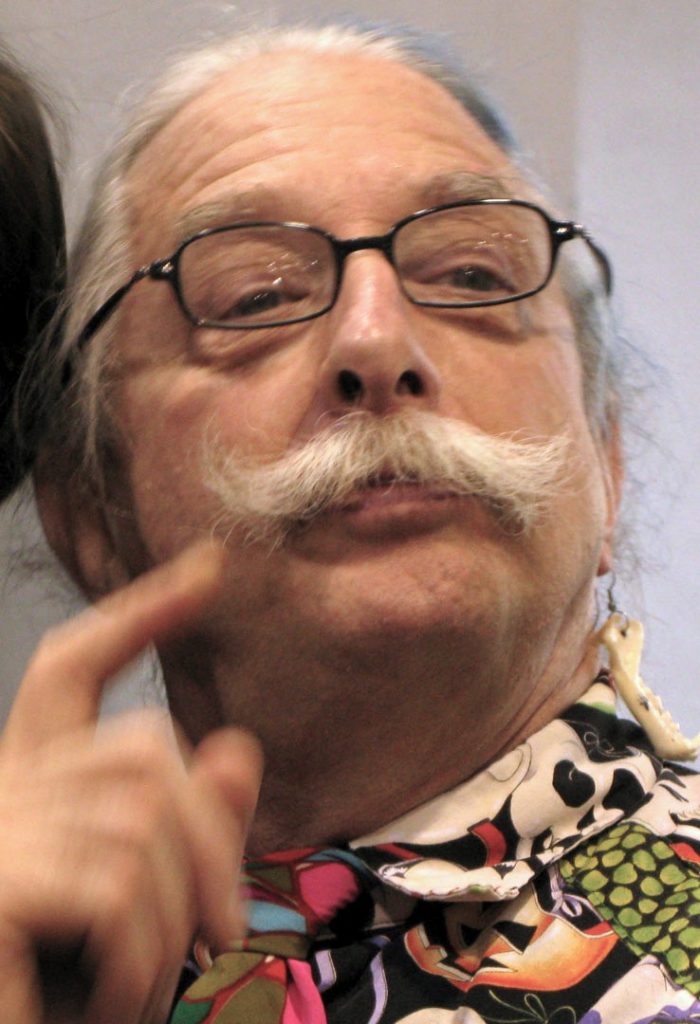

Patch Adams

I am a Doctor, but above all else I consider myself an activist for peace, justice and care for all people.

Hunter Doherty “Patch” Adams (born May 28, 1945) is an American physician, comedian, social activist, clown, and author. He founded the Gesundheit! Institute in 1971. Each year he organizes volunteers from around the world to travel to various countries where they dress as clowns to bring humor to orphans, patients, and other people.

My life has been a dance with humanity

Friends are my passion

Clown Mask by Patch Adams

Clown Care

Clown Care, also known as hospital clowning, is a program in health care facilities involving visits from specially trained clowns. They are colloquially called “clown doctors” which is a trademarked name in several countries. These visits to hospitals have been shown to help in lifting patients moods with the positive power of hope and humor. There is also an associated positive benefit to the staff and families of patients.

Humor research

Humor research (also humor studies) is a multifaceted field which enters the domains of linguistics, history, and literature. Research in humor has been done to understand the psychological and physiological effects, both positive and negative, on a person or groups of people. Research in humor has revealed many different theories of humor and many different kinds of humor including their functions and effects personally, in relationships, and in society.

Clown Doctors:

Shaman Healers of Western Medicine

Author(s): Linda Miller Van Blerkom

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Medical Anthropology Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Dec., 1995), pp. 462-475 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/648831 .

Accessed: 15/07/2012 12:23

[clowns, shamans,pediatriccare,medicalsystems, complementarymedicine]

PDF:

Clown as interpreters of emotions

Alberto Dionigi

P.A.T. Group – Department of Psychology, University of Bologna

Abstract

In recent decades, humour has come to be viewed not only as a very socially desirable trait for any human being but also as an important component of mental and physical health. Clown therapy represents a peculiar way of using humour in order to promote people well-being. Clown Therapy officially started in 1986, but it is thank to the well known 1998 movie “Patch Adams” that clown therapy has gained worldwide popularity. Nowadays, it is very easy to find clown doctors in hospitals and it is therefore paramount to define their status and role. When thinking about clowns in hospitals, people tend to see them as volunteers dressing in clown’s clothes whose main purpose is to improve hospitalised children’s and adults’ mood. In actual facts, clown therapy is much more than this. Every year many people express their interest in becoming clown doctors. Consequently, the necessity of creating adequate training courses has emerged. To this end, some Clown Care Units in Italy have founded an association called Federazione Nazionale Clown Dottori, which aims to establish the role and status of clown doctors, along with providing adequate training.

Key words: humour, well-being, clown doctors, clown therapy, clown care

Dr Thomas Sydenham, a famous physician who lived in 17th Century, used to say that the arrival of a good clown exercises a more beneficial influence on the health of a town than the arrival of twenty asses laden with drugs (Dionigi, 2009). This statement clearly shows how clown therapy is not a discovery of our time. Clown therapy is defined as the implementation of clown techniques derived from the circus world to contexts of illness so as to improve people’s mood and state of mind.

The birth date of clown therapy dates back to 1986 when Michael Christensen, a famous clown of the Big Apple Circus, created the Big Apple Circus Clown Care. The idea was realised after that a clown of Big Apple Circus was hospitalised in Presbyterian Hospital in New York. During his stay in hospital he was frequently visited by his fellow colleagues that came to his room dressing in their usual clown suit. During these visits, medical staff noted that the arrival of clowns in the hospital had a beneficial effect on other hospitalised patients: this unusual and incongruous kind of visitors amused patients and made them laugh. The most important consequence of these visits was that patients felt happier and since their mood had improved, they needed to take fewer drugs.

After that Michael Christensen founded the first Clown Care Unit (a medical support units of clowns), which started offering its services in New York in the same hospital where the fellow colleague of Michael had been hospitalised. Soon after, several Clown Care Units began to work in Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco and throughout the United States thus involving several tens of clowns who assisted hospitalised children and improved their hospitalisation period. Clown therapy soon spread across the globe and clown care units were founded in many other countries such as France, Germany, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom and so on.

In Italy, the first Clown Care Unit, called Fondazione Theodora, was set up in Milan in 1995. Inspired by it, other associations of clown therapy have been set up across Italy and many clowns have left the world of the circus and entered hospitals and health care settings to work as clown therapists.

I could go on forever about my love of books! The house is filled with books, and it’s a fraction of what’s waiting in West Virginia. If there is any topic you are curious about, I’m sure there is a book for you! In the video I mention Kindle. I’m not specifically promoting Kindle, just that I understand that some people like reading on tablets. I’m not tech savvy, and I love the feel of a book in my hand too much to give them up.

Clown therapy and health

Although physicians and philosophers have been making claims about health benefits of humour and laughter for centuries, these ideas have become increasingly popular only in recent decades. In 1979, Norman Cousins published an account of his recovery from ankylosing spondilitis following a self-prescribed treatment regimen involving daily laughter and massive doses of vitamin C (Cousins, 1979). The subsequent popularisation of alternative approaches to medicine has then gained humour, laughter and their therapeutic benefits widespread acceptance (Martin 2004). In addition, the medical world has begun to take more serious notice of the healing power of humour and the positive emotions associated with it (Martin 2007).

In many ways the hospital setting is the antithesis of the home environment. Illness and death often cast a shadow of intense seriousness, interfering with the expression of the full range of emotions. Experts suggest that on average a person laughs approximately 15 times a day (Dionigi and Gremigni 2010). In hospitals, however, this figure can drop to zero.

Hospitalisation is considered a negative event in life, usually causing distress that may become traumatic for children (Golden et al., 2006). Even a minor paediatric hospitalisation can have negative consequences on the emotional, behavioural, cognitive, and academic development of a child (Vagnoli et al., 2007). Feelings of tension, uneasiness, and fear are some of the many symptoms that children may experience during the hospitalisation period (Kain et al. 1996; Kain et al. 2000).

Parental anxiety is also very common during hospitalisation due to the perception of the child’s pain and their personal worries and fears (Lamontagne et al. 2003). In particular, if a child is to undergo surgery, they are likely to develop high levels of anxiety. More interestingly, some research has shown that children’s preoperative anxiety is usually associated with parental anxiety (Kain et al. 1996).

Hence, some hospitals have developed programs of humour support for hospitalised patients. It is nowadays very likely to find rooms provided with DVD players that plays comic movies and library shelves filled with humorous books. In addition, in recent years, clown therapy has become an integral part of the hospital setting. Clinical staff has noted that the main benefit of humour therapy is represented by its distracting approach, which keeps the patients’ minds away from concerns related to their illness and consequent depressed mood, thus promoting a balanced expression of emotions (Farneti, 2004).

Patch Adams (1998)

The true story of a heroic man, Hunter “Patch” Adams, determined to become a medical doctor because he enjoys helping people. He ventured where no doctor had ventured before, using humour and pathos.

Director: Tom Shadyac

Writers: Patch Adams, Maureen Mylander, Steve Oedekerk

Stars: Robin Williams, Daniel London, Monica Potter and more

The literature regarding humour in hospital wards across various age levels shows that not only patients and medical staff benefit from humour, but interactions involving humour between hospital personnel and patients promote an atmosphere in which laughter and humour self-perpetuate (Golan et al., 2009). Other investigations report that humour has beneficial effects on stress related to terminal illnesses (Bennet et al., 2003), on pain tolerance (Weisenberg et al., 1998) and on mental functions such as memory and anxiety (Fry, 1992). In paediatrics, humour is increasingly present in the hospital setting and it often employs clowns. Based on the assumption that humour is associated with the well-being of patients (Martin, 2001), there has been an increase in performances provided by ‘clown doctors’ in paediatric settings. The existing studies concerning clown performances suggest decreased levels of distress in the child and parents and increased cooperation of children who undergo medical procedures (Golan et al. 2009; Vagnoli et al. 2007; Vagnoli et al. 2005). These studies show that those children who benefited from clown performances felt less worried about hospitalisation, medical procedures, illness and their negative consequences; these children also reported a more positive emotional states (felt happier and calmer) than those who did not benefited from clown therapy. These results support the hypothesis that humour and specifically the clown doctor’s presence reduce the distress of hospitalised children (Golan et al. 2009; Vagnoli et al. 2005, 2007).

Research could be extended to verify whether the clown performance has positive effects on hospitalised children’s parents and their preoperative anxiety.

The clown doctor’s profile

Who are clown doctors and what exactly do they do? Clown doctors are highly skilled professional performers who have undergone an audition process and initial training to work in the sensitive hospital environment. Once they are allowed into health care settings, clown doctors collaborate with the medical and paramedical staff to allay the anxiety and fear that the hospitalised children and their family feel.

The distinction between clown and clown doctors is significant and important. The term ‘clown doctor’ specifically refers to:

• volunteers that have carried out a specific training in order to improve their psychological skills and their ability of clowning within the diverse professional contexts they may work, e.g. hospitals, communities, etc.

• non-professional artists who have been trained as a professional clown doctors;

• professional artists (therefore not volunteers) with a show-business or theatrical background that have been specifically trained in order to adapt their artistic skills to medical and clinical settings.

A clown doctor is therefore someone who (regardless of his/her qualification) operates in the context of distress using the art of clowning and integrating it with knowledge of psychosocial health so as to act on emotions and change them. Hence, clown doctors should be seen as providers of support and practical help during treatment programs for hospitalised children and adults. Play, spontaneity, light-heartedness, humour and creativity are the main ingredients in the healing process. Clown doctors act both as catalysts for change and as gauges of health along the way. Clown therapy is based on play

that fosters humour, creates a light-hearted atmosphere and relaxes the individual at both physical and mental level (Carp, 1998).

The purpose of clown therapy is to be ironic about medical practices in order to defuse certain states of anxiety that can be very distressful for children and adults who are suffering. It also aims to help their caregivers. This particular practice focuses specifically on the “healthy part” of the patient in order to influence the “affected part” and speed up their recovery process.

Clown doctors are not physicians. In fact, they are a special breed of performer and each of them develops a unique clown doctor persona. Everyone has an identifiable and unique personality, trademark and name e.g. Dr. Giraffe (ears, horns and a detachable tail), Dr. Chic (formal dress shirt, Scottish kilt and a French beret). In addition to their own costume, each clown doctor has a personal and decorated white medical coat. This makes the white coats of the medical staff less scary and, at the same time, identifies the clown doctors as a part of the medical team. Moreover, the clown doctor’s medical model has the purpose of parodying the medical routine in order to help children adjust to their new environment and the intimidating medical jargon and procedures. The clown doctors often carry a variety of props in their pockets or in their “doctor bags” e.g. slide whistles made from syringes; telephones made from stethoscopes; traditional musical instruments of all kinds (Carp, 1998). Essentially, any object, medical device or toy that is found in a patient room can be transformed and used as a theatrical tool. Finally and most importantly, all the clown doctors wear a red nose that is also called “the smallest mask in the world” (Farneti, 2004). It is the glue that holds all the clown doctor’s characters together.

The red nose or make-up mask of the clown, like a theatrical role or character, is both protective and liberating, enabling the expression of what lies buried beneath our real life roles. “Having something to hide behind is a vehicle, rather than an obstacle, to self-exposure. Illusion in theater does not lead to elusion of truth but to confrontation with truth” (Emunah 1994: 7).

Resources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patch_Adams

https://web.archive.org/web/20161018215310/http://www.simplycircus.com/sites/default/files/4_3.pdf